Description

Taken from from makkum website:

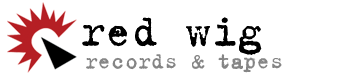

King Ayisoba – vocals, kologo

Abaadongo Adontanga – dancer, backing vocals, dorgo

Ayuune Sulley – sinyaka, backing vocals

Gemeka Abobe Azure – guluku + dundun drums

Ayamga Francis – djembe + bemne drums

Ghana’s ancient empire and the 21st century global express. The rhythms that created the past alongside the beats forging the present. In King Ayisoba, they all converge. Everything morphing into one. And on his new album, “1000 Can Die”, they stand together, history and today, side by side. The tradition hewn from the future.

King Ayisoba and his band know that traditional instruments are stronger than anything modern, says album producer Zea (The Ex’s Arnold de Boer). Playing them is a gift from God. They’ll take what they can use from electronica, from hiplife (the hugely popular Ghanaian style that fuses the local highlife music with hip-hop) but they won’t let it beat them, because they know what they have is more powerful. Their music is pulled from the ground.

The juxtaposition of the two on “1000 Can Die” shows the irresistible drive of both sides. The thick, squelching bass and beats that push under the older rhythms of “Anka Yen Tu Kwai” are overtaken by the guluku and dundun drums that bring in “Yalma Dage Wanga”, its rapid-fire melody dictated by Ayisoba’s voice and two-string kologo lute.

We wanted the drums leading and upfront all the time, not as exotic additions, Zea says. The sense of tradition always rises above everything.

That overwhelming sense of the past in the present has been the hallmark of King Ayisoba’s career. Born in Bolgatanga in rural Ghana, he was a prodigy on the kologo, playing locally until he’d outgrown the possibilities of the area. Moving to Accra, the country’s biggest city, he eventually released the song “I Want To See You, My Father”. There was nothing modern about it. No hiplife rap, no electronic beats. But somehow it conquered the country and brought the tradition firmly into the mainstream.

It was Song of the Year and Traditional Song of the Year, Zea recalls. He also had a song called “Modern Ghanaians” that said we shouldn’t forget the tradition. Instead we should use it to fight modern problems.

With that mantra, King Ayisoba became the unlikeliest star. His music was a strong weapon for Ghana’s traditions. What he wanted, though, was to play with a band, to bring what he called the “man-power” to give the full drive to his sound. On the album Wicked Leaders, with Zea producing, that’s exactly what he did.

After that Ayisoba toured Europe together with Zea, opening up solo, providing guitar, vocals and live electronics on stage, and Francis Ayagama joined King Ayisoba’s band on djembe and bemne drums.

Francis is young and he has a small studio. Ayisoba said he’d like to ‘chop’ some of my beats with the band. We tried it, then he and Francis started working on things. Sometimes beats first, sometimes the other way round, but always around the groove of the band. Ayisoba believed he’d show that the tradition was more powerful.

Piece by piece, the experiments grew into the juggernaut of 1000 Can Die. Guests brought new facets to some of the tracks. The trailblazing Nigerian saxophonist Orlando Julius adds a raw, reedy quality to “Dapagara”, while on “Wine Lange”, the only song not to feature kologo, Sakuto Yongo’s one-string gonju fiddle takes the music into a different, ancient dimension. The title cut features Ghanaian rapper/producer M3nsa alongside the shape shifting vision of legendary reggae producer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry.

We met Scratch in Amsterdam airport, Zea remembers. He and Ayisoba grabbed each other’s attention. We had a short talk, and they decided to do something together. It wasn’t planned. We already had M3nsa’s part on the track when we sent it off. That song created itself.

“1000 Can Die” builds into a sonic epic; after that the all-acoustic “Grandfather Song” arrives like a plunge into deep water.

It’s a preaching, Ayisoba explains. You can never cut the small stone. This means you have to stay strong, when you are big or small, they can never cut you when you are a stone.

Alone or with beats, ultimately the power that propels “1000 Can Die” comes from the band itself, from the sense of history that forms every piece of music. It’s there in every musician. They all go home and farm. They’re connected to the land, and the songs are part of the harvest they bring from the fields and from their own families.

Ayisoba’s grandfather played the kologo, Zea says. But only in the house. He was a healer, a shaman. People would come and tell him their problems. He’d make a connection with the spirits, then play and start singing, and his stories would include solutions.

It’s a force that Ayisoba has inherited. He’s absolutely compelling, charismatic. Not only in his imposing appearance, but in his kologo style – part rhythm, part melody – and singing. Whether the words are in Frafra, Twi, or his own style of pidgin English, the sense is always there: this is a man who has something important to impart. Every moment is intense and urgent. It leaps over the sounds of the album’s opener, “Africa Needs Africa“ and remains, gentle and soothing, on the acoustic last track, “Ndeema”.

Ndeema is the name of your wife’s house, where the father- and mother-in-law live, Ayisoba explains. If me and my wife get problem, the wife will go to her house and the father-in-law will support the wife. So this song is about how to solve the problem.

Perhaps there are solutions in the music. There’s definitely hope. On “1000 Can Die”, King Ayisoba is digging a new future from Ghana’s soil.